The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

Study the chapter for one week.

Over the week:

Activity 1: Narrate the Chapter

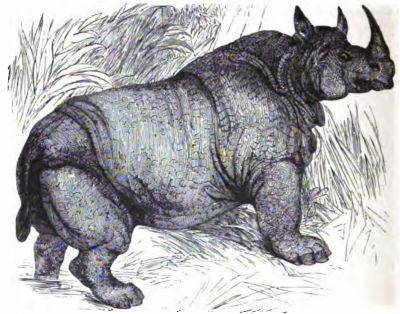

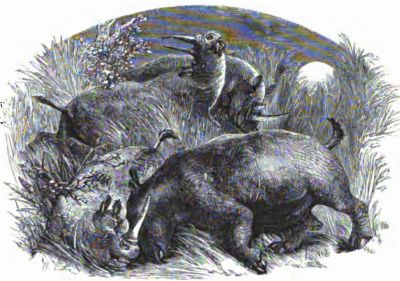

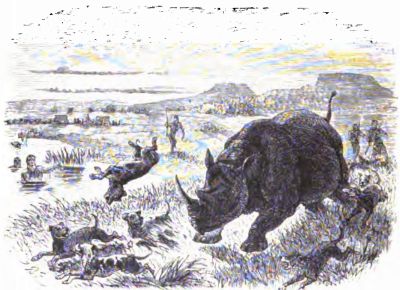

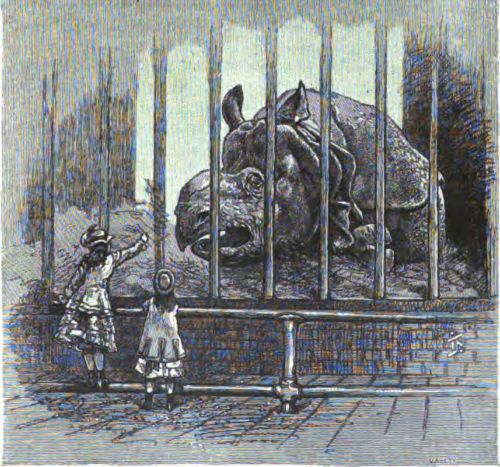

Activity 2: Study the Chapter Pictures

Activity 3: Observe the Modern Equivalent

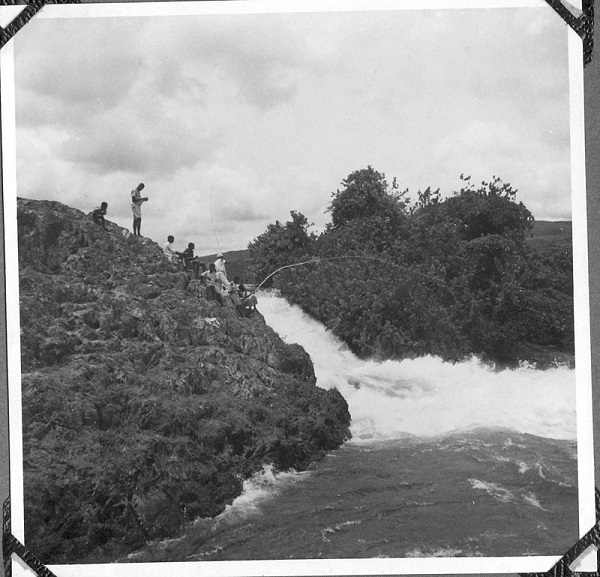

Activity 4: Map the Chapter

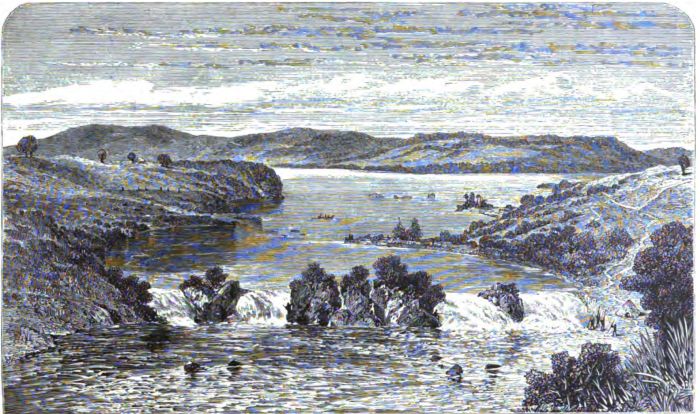

Find the location of Ripon Falls, a natural outlet at the northern end of Lake Victoria which flows into the Victoria Nile, formerly considered the source of the Nile River.

Activity 5: Map the Chapter on a Globe